Your age: 30

Number of pregnancies and births: 4

————–

“I hate using maps,” I said to him. Amongst sculptures and artifacts, oil canvases and mixed media, we wandered aimlessly and tirelessly. Hours passed like seconds. Nothing mattered to me but the air that he was breathing. The walls melted in the winter rain falling outside the plate glass windows, and the sun sank somewhere deep into eternity beneath the puddles of water. I followed him everywhere. The corridors seemed unending; like a house of mirrors that reflected a false doorway, one after the other. We passed through centuries of art, through wars and peace, across the world and back, and yet still, time loosed its hands and we lost grip of where we were, who we were, and even what we were. The only identities left were my reflection in his eyes, and his reflection in mine. Everything about him stuck to me like honey. Any time I turned a corner and he did not follow, the honey pulled itself into thin long strands of gold between us like spun sugar. This, I know, was when I slipped into love with him.

Now eventually, time returned. After the ink on the marriage certificate dried, bills were arriving in the mail, babies were crying, jobs were lost and discord began to settle in with the dust. I needed guidance. I looked in my reflection and saw a mother of three young babies with more stretch marks on her belly than pennies were in her bank account. I was stuck in a job making a living but not actually living. Life spun on an axis of baby bottles and stacks of mounting bills, all co-existing in an apartment with less than 1000 sq ft of living space. The grip around my neck could not have gotten any tighter without cutting off all of my air supply. That is, until I found myself pregnant for the fourth (and last) time when my youngest daughter was a mere four months old.

But I still hated maps. One day in a Psychology class, I read that spatial orientation can affect one’s ability to properly read and follow maps. I self-diagnosed this as my problem. Every road has a map; every step goes in a direction. My inability to identify with direction was surely my downfall, or so I assumed. Maybe my failing spatial orientation was the missing piece of my maternal progression. Maybe the two were meant to be entwined, and the thread between my failures and successes unraveled at some point in my life. Maybe I needed to stay positive. I fixated on the latter. If maps were written in a language that I could not comprehend, I could find another direction; one that would supersede my inabilities and guide me through the dark corridors that held the centuries of my soul, and now, the corridors of four very small children. No one is born into the earth without carrying a seed of all who were before him. I owed it to my children to find myself. This, I reasoned, was why I needed a different sort of compass to find my way. The ancients had sundials. Others had wind currents. Surgeons had x-rays, and lovers had intuition. I, however, had none of these things. I only had the stickiness of my soul and clouded words that sometimes became cohesive thoughts. As I grew in sentence structures, words became my guide.

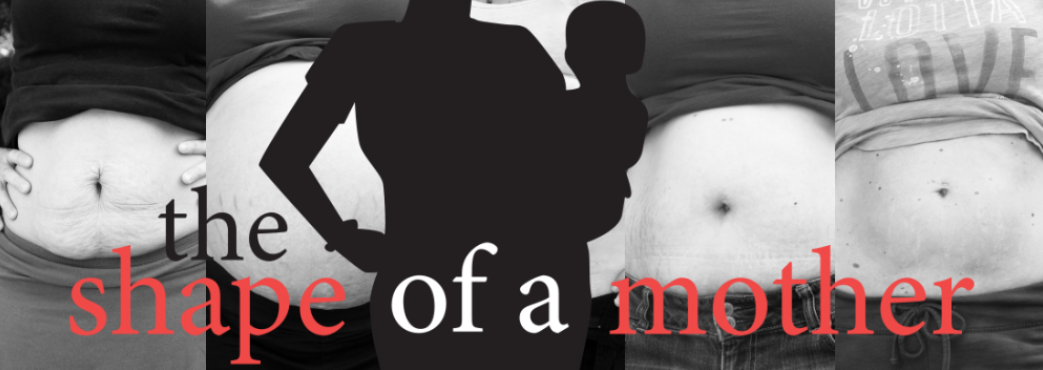

Martin Luther King once quoted Amos at the Mason Temple in Memphis, TN when he said, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” It was a quote so poetic that it sank deep into my thoughts by the mere symphony that seemed to resonate from the syllables. Later in life, however, it resonated with me for different reasons. I slowly began to understand the booming voice of Dr. King and the purpose for which he gave his life. What I didn’t understand, however, was how we as mothers never adapted his passion and sharpened his words as a weapon to defend ourselves from our own superficial society. Dr. King identified the poor of America as one of the wealthiest group of people on the earth because of the strength in their combined numbers. “Never stop and forget that collectively, that means all of us together, collectively we are richer than all the nations in the world, with the exception of nine.” Collectively, we as mothers are richer than all the men in the world because of what we have given to our societies. As the poor are trampled upon because of their lacking economic status, so we, too, are trampled upon because of our lacking status in magazine covers, Victoria’s Secret catalogs and a number of other superficial outlets. There is no public praise of sagging breasts that gave our babies their first meal; thighs with cellulite because we rocked our babies to sleep every night instead of handing them to a nanny; deflated bellies that held our children so close to our hearts that their muscular walls gave out and left us with empty skin. There is no acknowledgment of mothers because it seems we denote something from which we all search frantically to run – true love, unconditional love, love that extends its arms from time into eternity. We are a few generations that span across a 16 and Pregnant era, a “Love Kills Slowly” era, an era of sordid affairs, broken homes, and an era in which The Real Housewives have overtaken the maternal role of June Cleaver, Carol Brady and even Lucille Ball. But we are the richest group of human beings on the face of the earth, if for no other reason than our ability to bond with a human life. When we stop scrutinizing ourselves long enough to look around us, absorb what is hurting the mother beside us, and acknowledge that we, too, suffer from the same – this is when our justice will roll down like waters and our righteousness will flow like a mighty stream. When we embrace ourselves, our streaming stretch marks that roll down our bellies, our voices that overtake like a mighty stream in our children’s lives, then and only then will we see freedom in ourselves and in the world around us.

It is vital for us as women to return to the core of ourselves, and not merely in a moment of gratitude. In band societies, such as the San of the Kalahari Desert, the hunter who kills an animal to provide for his family is not the owner of the kill. Rather, the maker of the arrow that was used in the kill is the owner of the meat that is brought back to the tribe. Let us always remember that our children are our arrows. No matter what religion you are, remember the Psalm of King David that said, “Like arrows in the hand of a warrior, so are the children of one’s youth. Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them; they shall not be ashamed…” (127:4-5). Let us never be ashamed of who we are, where we are, or what we have given to our world around us. Though it takes a village to raise a child, let not our society take the gratitude that is to be bestowed upon each of us as the creator of the arrows. Let us teach the world more than how to raise a child – let us teach them to respect the shape of a mother by first respecting ourselves.